In the neoliberal era and the wake of the 1989: Code of Conduct on Images and Messages Relating to the Third World (updated in 2006), many development agencies are abandoning the use of exploitative shock imagery, and adopting a new strategy of deliberate positivism. This is due to widespread criticism of using ‘development pornography’ – exposing and exploitative images- which reinforce the South as the ‘other’ for the motivation of financial gain. However, there is debate over if this new wave of marketing actually combats the criticisms of pornography porn, and if it is effective in mobilising the public to act and donate.

https://www.wateraid.org

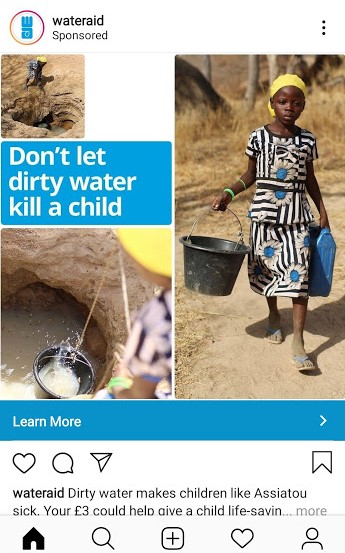

There are many advantages and disadvantages that can be argued for both methods of presenting poverty. One main criteria that must be considered is a campaign’s ability to contextualise the suffering and inequality, as many campaigns come short on this by simply portraying an individualised snapshot. In this respect, there is a danger in using positive emotions as it tends to provoke low intensity emotions, as it appeals to the individual rather than to a collective responsibility. This has been explored by Chouliaraki (2010), who details how this makes development efforts appear apolitical, lacking the wider social and political context in which the poverty is being experienced. For example, in Photograph 1 we are understanding development efforts in the portrayal of one child’s joy, and therefore this allows us no temporal or spatial context of the poverty, encouraging the consumer to engage individually rather than promoting understanding of the political actors that may be involved. The medium also focuses on a child, which is a pre-existing strategy in the field of development to remove the political context, as adults would be seen as politically able and motivated, whereas a child is seen as innocent and removed. Representing the individual and the youth is a consistent theme within Water Aid’s marketing (as can be seen in Photograph 2 and the quote below), therefore taking no responsibility to educate and engage the wider public with the political context of poverty creation and elimination, which can be widely criticised for compartmentalising the problem.

“Azmatun spends three hours each day collecting water from the nearest river – and it isn’t even clean. This puts her health at risk and leaves her no time for school.”

Quote used in Water Aid’s online marketing campaign 2020 – view their website here

This wave of deliberate positivism was founded with the intention of rebranding images of the South, moving away from portraying them as vulnerable and as ‘other’ by using images that show people as happy and empowered (Cameron and Haansta 2008). This aims to offer the global South a form of agency and representation which combats their dis-empowerment in the development process. However, Water Aid continues to undermine this movement by sustaining its use of emotive language in its humanitarian communication, as can be seen in Photograph 2.

View their full Instagram account at https://www.wateraid.org/uk/media

Whilst appealing to our sense of empathy, there are two main reasons why using images and slogans portraying suffering often are ineffective in mobilising public donations and actions. The first of these is that our Western viewpoint has conditioned us to be critical when considering taking action, by positioning ourselves as the victims of a marketing ploy, and simultaneously critiquing and boycotting agencies for a lack of moral consideration (Bruna Seu 2010).The second of these is a phenomena coined ‘compassion fatigue’, in which the consumer no longer feels empathy due to a saturation of similar images. This desensitises the audience and therefore no longer has the shock appeal, and is rather just observed and critiqued (Potter 2001).

Although Water Aid have claimed to focus their media efforts on promoting universal human rights (as can be seen at https://www.wateraid.org/uk/media), they continue to use exploitative slogans and fail to address or portray the wider political and social dimensions to poverty and human rights abuses.

Bibliography

- Bruna Seu, I. (2010). ‘Doing denial’: audience reaction to human rights appeals. Discourse & Society, 21(4), pp.438-457.

- Cameron, J. and Haanstra, A. (2008). Development Made Sexy: how it happened and what it means. Third World Quarterly, 29(8), pp.1475-1489.

- Chouliaraki, L. (2010). Post-humanitarianism. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(2), pp.107-126.

- Potter, R. (2001). Progress, development and change. Progress in Development Studies, 1(1), pp.1-4.